The Future is Fungus

Any time a major historical event takes place, it is not unusual to see a wave of predictions from the horror media and fanbase regarding the next trend in content.

Pre-pandemic it seemed as though techno-horror was on the rise. Films like Leigh Whannel’s Upgrade and Invisible Man, and Alex Garland’s Ex Machina presented a terrifyingly plausible dystopian future where the whims of wealthy geniuses become a threat to themselves and humanity as a whole. Granted, the recent, gratuitous space travel and overall worrying behavior of billionaires in this country still keep these films very much relevant. But it seems the pandemic has overall shifted our creative gears to the other end of the spectrum in the form of Eco-Horror.

In many ways, Eco horror is the antithesis of techno-horror We went from the fear that our own creations would turn on us, to the existential realization that we were never the one’s in charge in the first place. Now, this is in no way a new concept, just one that has quickly gained traction within the last year. An earlier and unquestionably influential example of pre-pandemic eco-horror would be Alex Garland’s sophomore masterpiece, Annihilation. Annihilation seemed to be one of the first of the modern wave of sci-fi, which featured a biological threat unbound by human reason and emotion that would eventually consume and absorb all life on earth, robbing humanity of it’s autonomy. Garland’s choice to follow up his robotic debut of Ex Machina with Annihilation seemed almost prophetic in hindsight. While the bio-threat in the film is apparently introduced extra-terrestrially, more recent eco-terror films suggest that the threat is already living among us and may have been here longer than we have.

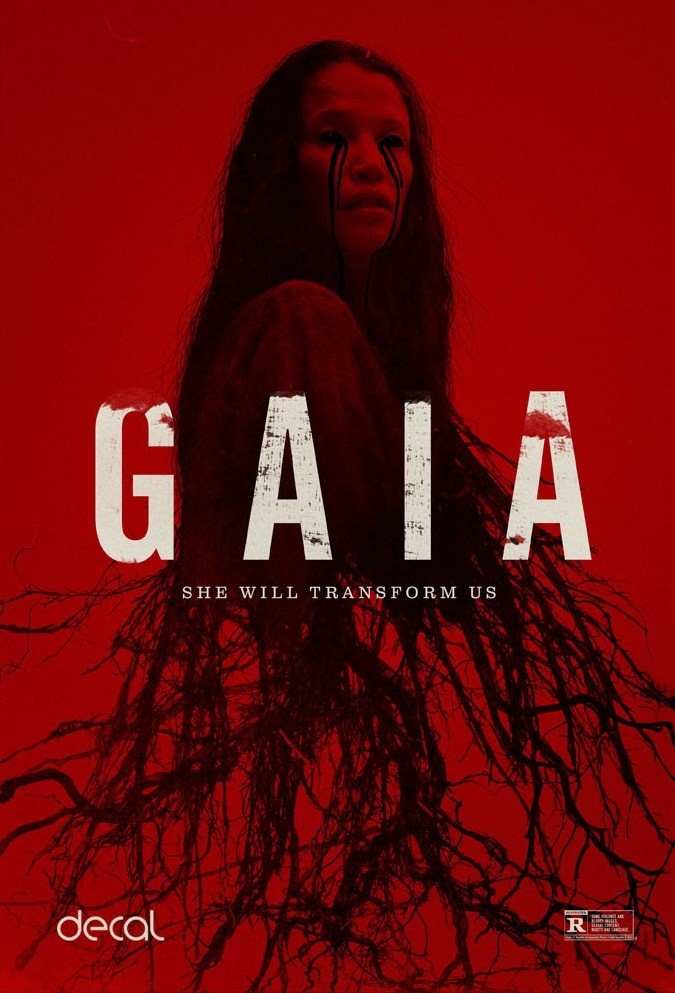

While the previously mentioned films were a result of being on the apparent precipice of a technological and scientific renaissance, the pandemic reignited a primal fear of mother nature. This could explain the heavy folk-horror influence in these films. One of the side effects of our collective existential crisis, is the suspicion that we have taken our understanding of science and nature for granted and that the earth still possesses a cornucopia of yet undiscovered threats. Two recent films released in the past several months that fit very firmly into this category, are Ben Wheatley’s In the Earth and Jaco Bouwer’s, Gaia.

In the Earth is in every way a pandemic-era film both in content and the because the entirety of production took place within Covid times. While a mysterious (and familiar) disease ravages the city, a pair of park scouts venture into the wilderness on a search for a scientist researching fungal systems. After a seemingly random attack, the pair find themselves in a dire situation and must put their trust in a stranger they encounter in the woods. Although initially suspicious, the pair follow the stranger to his encampment and accept his medical treatment as well as food/water. Unfortunately, they quickly realize that their trust has been greatly misplaced as the man drugs them and begins performing bizarre rituals. After a narrow escape, the two find themselves at the research camp they had initially been searching for. Here they learn that their captor was in fact the unhinged ex-husband of the elusive scientist. She explains that after coming into contact with a strange mist excreted by a fungus native to the region, the man had what seemed to be a very bad trip, after which he deteriorated into an extreme zealotry. He began worshipping the organism as if it were an old God requiring sacrifice. With injury and isolation delaying their escape, the scouts soon realize that the wilderness that surrounds them may have more sentience than they originally realized.

Although just as anxiety ridden as many of his previous films, In the Earth is a more atmospheric endeavor for writer/director Ben Wheatley. The unnamed pandemic that ravages the city is not a major plot point and is instead used as well executed plot device to infuse a sense of claustrophobia and otherwise explain the heightened hysteria and brutality committed by and against the characters with a Ben Wheatley signature glee.

The 2021 South African film Gaia possesses an eerily similar concept, albeit with far more body horror influence. After embarking on a surveillance mission into the South African wilderness, a forest ranger finds herself injured and separated from her partner. She is rescued by a pair of father and son survivalists who bring her back to their cabin to recuperate. The woman quickly learns that the jungle contains a full eco-system of phosphorescent creatures that seem to be the product of some ethereal fungus. As the woman learns more about her rescuers and the danger that surrounds them,  she learns that the father has fallen into a similar form of idolatry as featured in In The Earth. The father’s attempt to contain and understand this all-consuming fungus has evolved into over-zealous worship. Overwhelmed by her new surroundings, and the realization that this potentially sentient fungus has already taken root within her body, the ranger struggles to find a way to escape the many dangers surrounding her. While In The Earth waits to confirm the otherworldliness of the biological threat, Gaia shows it’s hand pretty early on, sporting some fairly enchanting creature designs. The alarmingly invasive organism seems heavily influenced by Garland’s Annihilation and potentially even 2008’s The Ruins. Despite the two films’ considerably similar plots, they manage to explore a myriad of independent themes. From suspicion and distrust in the wake of an impending global collapse, to the difficult choice between self-preservation and self-sacrifice.

she learns that the father has fallen into a similar form of idolatry as featured in In The Earth. The father’s attempt to contain and understand this all-consuming fungus has evolved into over-zealous worship. Overwhelmed by her new surroundings, and the realization that this potentially sentient fungus has already taken root within her body, the ranger struggles to find a way to escape the many dangers surrounding her. While In The Earth waits to confirm the otherworldliness of the biological threat, Gaia shows it’s hand pretty early on, sporting some fairly enchanting creature designs. The alarmingly invasive organism seems heavily influenced by Garland’s Annihilation and potentially even 2008’s The Ruins. Despite the two films’ considerably similar plots, they manage to explore a myriad of independent themes. From suspicion and distrust in the wake of an impending global collapse, to the difficult choice between self-preservation and self-sacrifice.

The one theme that these films all seem to have in common is the concept that surrendering control to a collective unconscious is ultimately inevitable and the wide array of ways humans cope with the futility of that reality. This oddly specific sentient fungus theme has even crossed over into the literary world, appearing in the popular bestseller by author Silvia Moreno-Garcia, Mexican Gothic. The philosophical roots run far and deep in this subgenre and due to increased international trade and military activity, there has been a small wave of scientific discoveries of fatal fungal attacks on multiple species around the world. So it is entirely possible that we will get even more fungus films as they become closer and closer to reality.